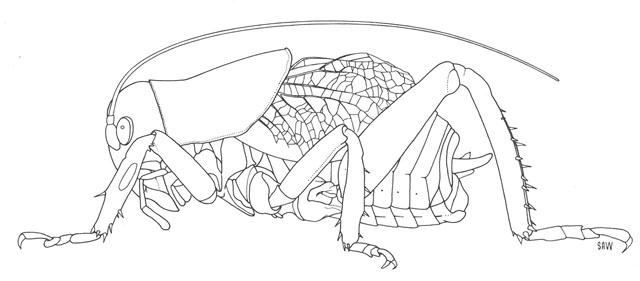

Hump-Backed Grigs:

Cyphoderris buckelli. Buckell’s Grig. Drawing of male

by Susan A. Wineriter, University

of Florida.

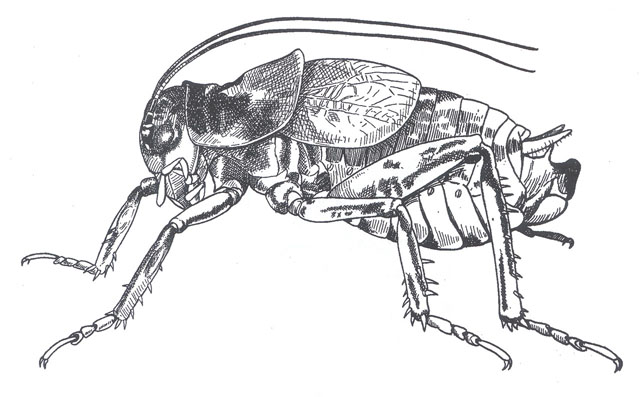

Cyphoderris monstrosa. Great Grig. Drawing of male, by

Mary Foley Benson. Fig. from Gurney 1939.

Hump-Backed Grigs

come from the family Prophalangopsidae, and there are three species that are

found in North America, all of which are in

the genus Cyphoderris. They can be found in coniferous forests, or in

high altitude sagebrush in the north western part of the United States, and extending up into Canada.

Hump-Backed Grigs

are nocturnal insects, and are rarely found during the day. They hide in

burrows, but come out at night. The males are found chirping away on tree

trunks or anything else that protrudes from the ground. They always sit head

down when chirping, and through the night will climb higher and higher until

they are out of reach.

It’s easy to tell

whether an adult grig is a male or a female. If the grig’s wings cover half or

more of its abdomen, then it’s a male. But if its wings are miniscule, then it

is either a female, or if it is small, then it is a nymph.

One interesting

thing is that it’s also pretty simple to figure out whether a male has mated

yet or not. You just lift up the upper wings to uncover the hind wings, and if

the hind wings are damaged at all, the male has mated before, but if the hind

wings are undamaged, then the male is a virgin. The reason for this is because

when grigs mate, the female will chew on the hind wings of the male.

The chirping is a

high pitched trill that lasts several seconds, stops for a moment, then starts

again. “Eeeeeeeeeeee! Eeeeeeeeee! Eeeeeeee!” The sound can be a little

unnerving, as it sounds anything but nice, and even the sight of these

creatures aren’t that friendly, but they really are quite harmless.

You can hunt them

at night by following their sound, but if you flash them with a light, they

will stop their song, and will not start up again for a few minutes. The way I

hunt them is I either shine the light on the ground in front of me or don’t

have my light on until I pinpoint what tree the grig is on. Once you have

pinpointed the tree the grig resides on, you can search the trunk with your

light.

Again, though they

look quite fierce, they are quite harmless, and will only bite if grabbed the

wrong way. The bite doesn’t even hurt, but is merely a little surprising, and

may cause you to drop the grig. Just grab it by its thorax with its legs held

against its body, and drop into an awaiting container.

The succession of

trills produced by the male are made at wing stroke rates of 50-75 (at 77 ºF) a

second. The forewings have both a “file” and “scraper” which produce the sound,

and will amplify and broadcast the trills; the right and left forewings both

have equally developed files and scrapers. They will alternate between which

wing is on top at rest. To what extent the grig will switch between the left

and right files is not established. This action is called “switch wing

stridulation”.

Though scientists

have separated the genus Cyphoderris into three species, it is most

likely that all came from the same created kind. There are only very minor

differences between the three different species, but it is still interesting to

examine these, and to see what diversity God has put in his creation.

The species of grig

that will be found in the Cascades of Oregon and Washington,

and specifically Paulina

Lake, will most likely be

the Great Grig (Cyphoderris monstosa). But just in case of undocumented

biogeography, here’s a key that shows some subtle, but interesting differences:

Lateral view of male subgenital plates of Cyphoderris.

Fig. from Morris & Gwynne 1978.

Not only are the

back ends of the three species different, but their songs too. The songs of C.

strepitans and C. buckelli are nearly indistinguishable, but there

is a difference between the song of C. monstrosa. At any temperature, C.

monstrosa has the higher pulse rate. Though a grig’s song is not as reliable

as the Snowy Tree Cricket’s chirp is, it does follow a pattern. The warmer it

is, the more pulses per second.

Relation of pulse rate and temperature in the calling

songs of hump-winged grigs. (S is from Spooner 1973.) Fig. from Morris &

Gwynne 1978 (slightly modified). Converted to Fahrenheit.

Truly God has blessed us with a diverse and

abundant amount of creatures. Everywhere we go we find different kinds of

insects. In some places you might find field crickets, other places tree

crickets, or katydids, or even cicadas. And last, in the Cascades and

elsewhere, you find the Hump-Backed Grigs. God has created a symphony for us to

enjoy at night, and to lull us to sleep. God is wonderful!

No comments:

Post a Comment